Enterprise AI keeps getting framed as a model problem. Bigger models, better prompts, smarter reasoning. But most failures in production have nothing to do with intelligence. They happen because intelligence alone doesn’t translate into reliable execution inside real business systems.

That gap between reasoning and execution is where most enterprise AI efforts stall, and it’s why orchestration has become the most important layer in the stack.

Vernon Keenan published a piece that should be required reading for anyone trying to make sense of enterprise AI right now. His argument: the "Salesforce Capitulated on LLMs" narrative fundamentally misunderstands how enterprise AI works.

The category error, as Keenan puts it, is that most of the market evaluates enterprise AI through the lens of personal AI. They see a chatbot, type something, get a response, and assume magic is happening in the black box. Enterprise AI has never worked this way, not reliably at scale anyway, which is really why the slap an agent on it approach continues to fall short in production environments.

Keenan nails this, and the implications extend even further than the technical layer he's focused on.

The Foundation: Why Orchestration Matters Technically

According to Keenan, Muralidhar Krishnaprasad, CTO of the Agentforce Platform, framed it this way: "People always thought LLMs were the thing—that with LLMs, you can do everything. But the reality is, it's really hard to take the power of the LLM and make it work for businesses."

The answer is the orchestration layer: getting the right data at the right time, deterministic controls, observability, and orchestration of agents with humans. This isn’t about loosely wiring components together. It’s about building enterprise-grade orchestration infrastructure that enables controlled, observable, and deterministic execution of AI workflows inside real business processes. This is what Salesforce is building with Agentforce and Agent Script, applying enterprise-grade orchestration principles directly inside the system where work already lives.

According to Keenan, the critics who called this a retreat from AI misunderstood what was happening. Embedded architectures were always going to require deterministic control layers, and that's not a weakness in the approach, it's what makes enterprise AI deployable in the first place. Even though some vendors hype pure LLM-centric products, those approaches haven’t demonstrated reliable enterprise performance at scale.

Keenan's analysis is exactly right, and it sets up a question worth exploring: once you have the technical orchestration layer in place, what comes next?

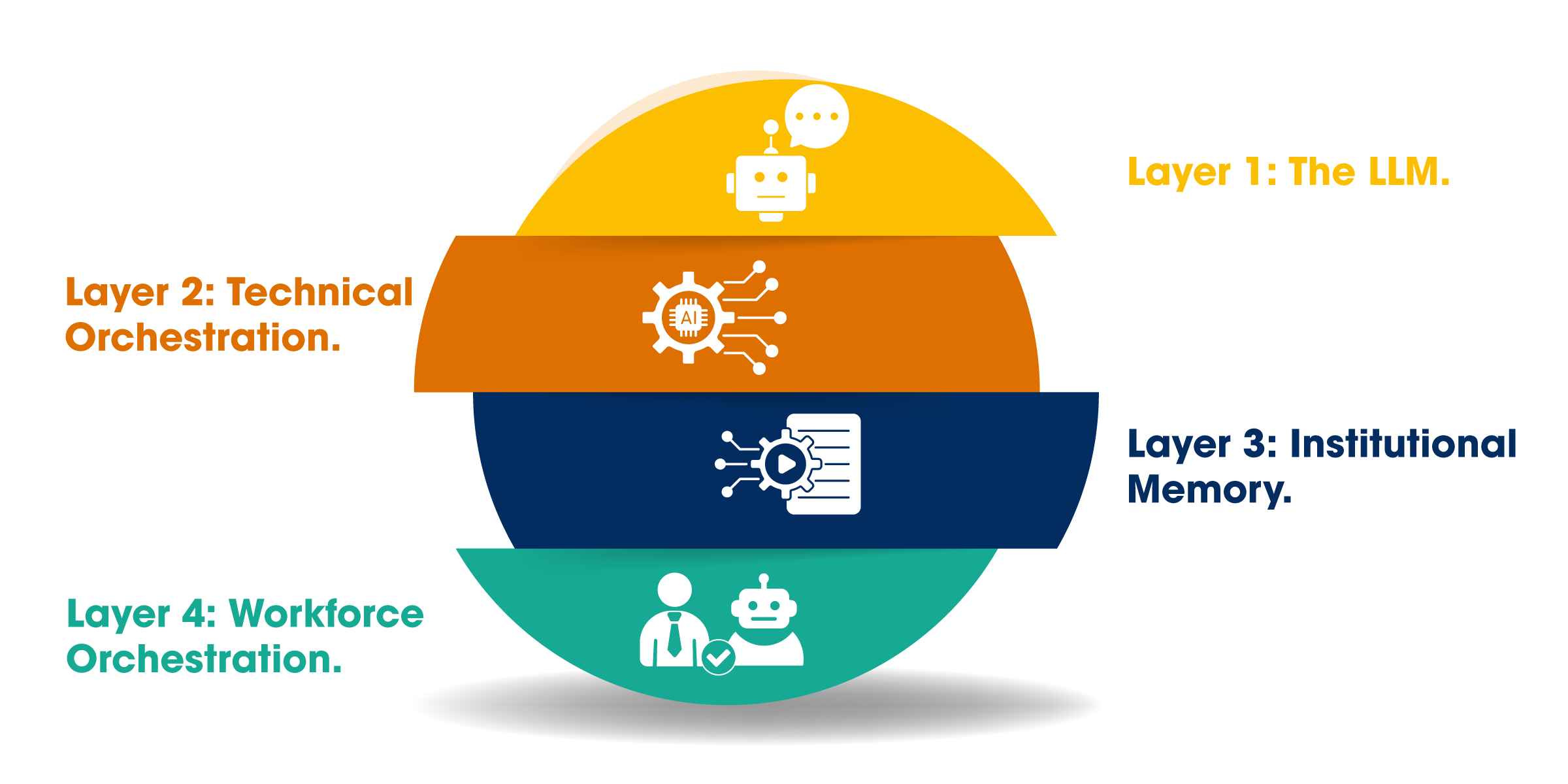

The Four Layers

The way I see it, there are four layers to getting value from the new future of work, and understanding how they stack helps clarify where the real work is and who's thinking about this correctly.

Layer 1: The LLM. The raw reasoning capability that makes everything else possible. It's what allows digital workers to interpret, understand context, and take action in ways that weren't possible before.

Layer 2: Technical orchestration. This is what Keenan's article is really about, and what Salesforce is building with Agentforce. His four components: getting the right data at the right time, control, observability, and orchestration infrastructure, all make AI work reliably in production.

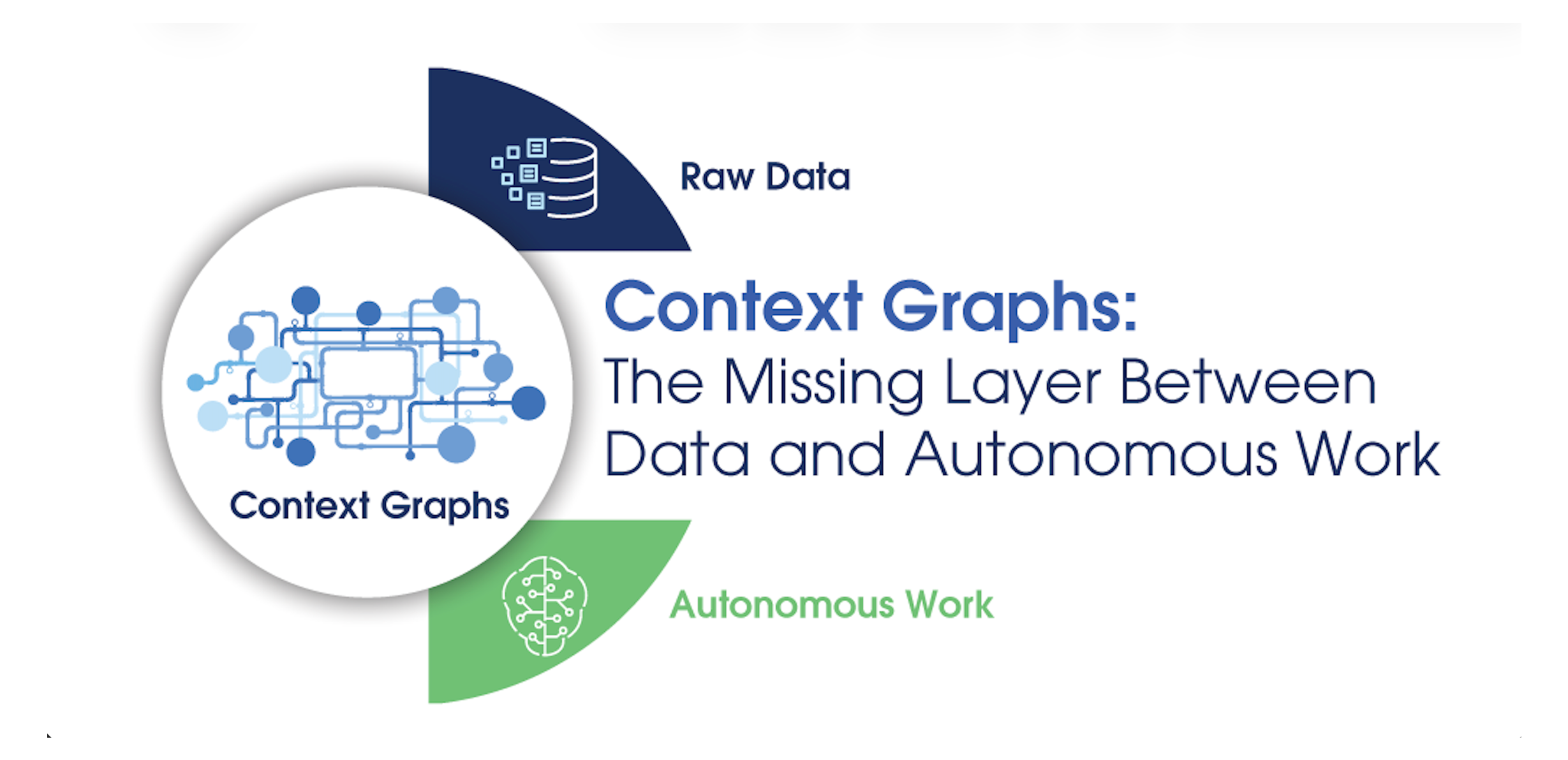

Layer 3: Institutional Memory. What matters at this layer is not just access to information, but understanding why decisions were made, how judgment evolved, and what customers expect based on past interactions.

Layer 4: Workforce orchestration. Designing, managing, and scaling blended human-digital teams, with job descriptions, success criteria, managers, coaching, and measurement. It's the layer where the business value happens, and the one most companies haven't figured out yet.

Keenan makes a compelling case for why Layer 2 matters, and he's right. What I’d add is that technical orchestration alone is not sufficient. Enterprise AI also needs a clear place where humans and digital workers collaborate in the flow of real work, which is why Slack matters so much to Salesforce’s strategy. The coaching, feedback loops, and real-time adjustments that turn a mediocre digital worker into a high performer happen in the collaboration layer. Having a hub where the blended workforce works together day to day isn't just convenient, it's where institutional memory gets built and where humans stay connected to the work their digital teammates are doing. That's why we're building on Agentforce.

Where the Value Lives

LLMs will become widely accessible, and technical orchestration will become table stakes as every platform vendor attempts to build similar capabilities. Institutional memory, though, the understanding of why your organization does things the way it does, that's something unique to your company. The organizational capability to manage a blended workforce, the humans who can articulate the why behind work, coach digital workers, and design outcomes across human and digital labor, is the talent paradox at the center of all this: you cannot direct a digital worker if you don't understand the why behind the work. This is the part that catches most people off guard, because the assumption is that AI reduces the need for human expertise, but the opposite is actually true. The humans who can manage digital workers effectively are the ones who understand the work deeply enough to explain why it matters, not just what needs to get done. As more organizations deploy digital workers, demand for these humans is only going to increase.

This distinction becomes concrete when you move from theory into operating reality. At Asymbl, we saw this firsthand when we onboarded Theodore, our Agentforce SDR. We assigned a human to manage it. Mitch Canaday, an Sales Development Representative (SDR) leader at Asymbl, met with Theodore weekly, fed it information, updated messaging, and coached it to perform better over time. That experience made Mitch more valuable, not less, which is why he ended up getting promoted. Without that kind of human oversight, digital workers become what we call zombie agents: decayed performers that introduce risk instead of reducing it. When a new employee struggles, you don't abandon them, you invest time in understanding what's going wrong, you adjust their approach, and you help them improve. Digital workers need the same kind of attention, and very few organizations are approaching this work with the necessary rigor today.

We deliberately use digital labor instead of agents because the language really does shape how you think about the problem. When you say agent, you tend to invite IT ownership and implementation thinking, but when you say digital labor, you invite business ownership and workforce thinking. You wouldn't implement an employee, you'd onboard them, and the same logic applies here.

Keenan's argument that orchestration was always the point holds up well, and Salesforce is building the technical orchestration and the collaboration hub that makes it possible. The question now is what you're building on top of that foundation. The companies that figure out workforce orchestration first, who invest in the humans and the institutional memory that make digital labor work, will have a compounding advantage that's genuinely hard to replicate.

FAQs

Leaders Are Asking About Digital Labor